Realising the transformative potential of nature-based solutions (NBS) requires unpacking the ways initiatives too often build from ideas that require injustice, such as the logics of racial capitalism. In this special blogpost, guest author Isabelle Anguelovski discusses findings from her forthcoming collaborative paper on why NBS must reckon with legacies of racial and ecological injustice.

The Injustices of Nature-Based Solutions: A Racial and Ecological Reckoning

NBS and ecologies of segregation

Nature-based solutions (NBS) are increasingly promoted as ideal interventions for climate adaptation, biodiversity preservation, and urban livability. Yet despite their promises, they are frequently embedded in logics of racial capitalism [1], reproducing rather than repairing long-standing environmental injustices.

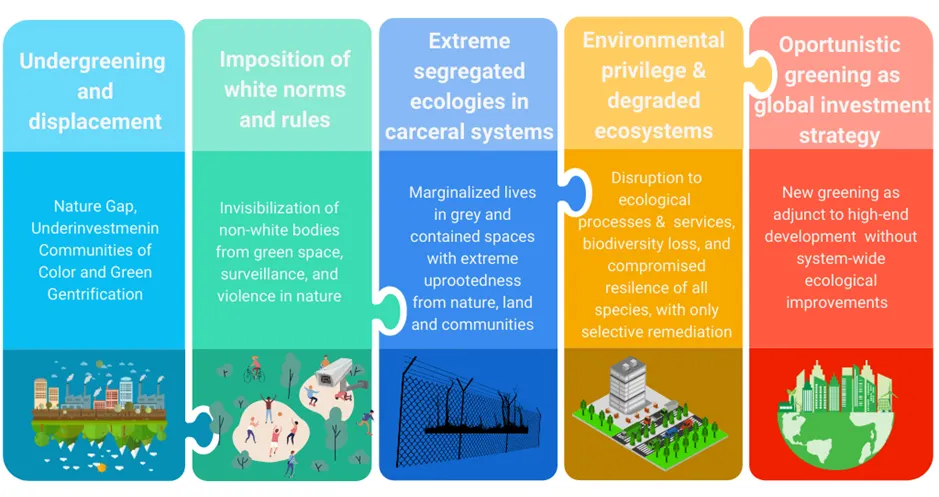

Drawing on research across Europe and North America, we find that five major pathways of injustice (Figure 1) define how NBS are currently designed and implemented: under-greening and displacement, imposition of white norms in nature, degraded ecologies, carceral segregation, and opportunistic greening. Together, they form what we call ecologies of segregation — spatial and ecological systems that entrench racialized inequality.

Figure 1: Ariel view of the concept for 11st Street Bridge Park in Washington D.C., which aims to reduce structural barriers to social and economic mobility to build a more equitable city. Photo source: Building Bridges Across the River https://buildingbridgesdc.org/

NBS and ecologies of segregation

Nature-based solutions (NBS) are increasingly promoted as ideal interventions for climate adaptation, biodiversity preservation, and urban livability. Yet despite their promises, they are frequently embedded in logics of racial capitalism [1], reproducing rather than repairing long-standing environmental injustices.

Drawing on research across Europe and North America, we find that five major pathways of injustice (Figure 1) define how NBS are currently designed and implemented: under-greening and displacement, imposition of white norms in nature, degraded ecologies, carceral segregation, and opportunistic greening. Together, they form what we call ecologies of segregation — spatial and ecological systems that entrench racialized inequality.

Figure 2: Framework for ecologies of segregation in NBS

Problem #1: Undergreening and displacement

First, there is a dual problem of under-greening and green displacement. Historically marginalized neighborhoods — often Black, Latinx, or Maghrebi — are frequently deprived of quality green infrastructure, with their parks smaller, more paved, and lacking ecological function [2]. This “nature gap” stems from long-standing municipal neglect and redlining or segregation legacies.

When these areas do receive investment, research has shown that greening often leads to or contributes to green gentrification: rising land values attract real estate speculation and whiter and wealthier residents, forcing longtime residents out. In cities like Philadelphia, Copenhagen, and Barcelona, climate-resilient infrastructure has become a vehicle for displacement rather than inclusion, shifting racialized communities to grey, climate-exposed peripheries.

Problem #2: Imposition of white norms and rules

Second, many NBS tend to reproduce cultural and symbolic exclusions by imposing white environmental norms. Rather than recognizing diverse socio-natures, new green spaces often erase the cultural practices and spiritual relationships that many racialized communities have with nature.

In Washington, Montreal, Lyon, and Barcelona, we find that racialized residents report feeling unwelcome in newly renovated green areas, policed for their presence or activities, and excluded by design choices that prioritize quiet, passive recreation. Muslim women, Black families, and migrant communities face surveillance and harassment in spaces that should foster well-being. These experiences reveal how green spaces remain coded as white, reinforcing environmental privilege through both material access and cultural control.

Problem #3: Extreme segregated ecologies in carceral systems

Third, these exclusions often coincide with degraded urban ecologies in racialized neighborhoods. In many U.S. cities, neighborhoods with higher proportions of Black and Latinx residents show reduced tree canopy, fewer species, limited biodiversity and, in return, lower climate protection [3].

Historic redlining is linked not only to heat vulnerability and flooding but also to ecological impoverishment, where wildlife habitats, soil quality, and air conditions are significantly worse. These ecologies of neglect deepen environmental burdens while reducing community resilience to climate impacts.

Problem #4: Environmental privilege and degraded ecosystems

Fourth, extreme forms of carceral segregation represent a critical, often overlooked dimension of ecological injustice. Prisons, overwhelmingly filled with racialized and low-income individuals, are sited in toxic, degraded environments and expose inmates to unsafe water, polluted air, and lack of access to nature. While some carceral facilities introduce gardening programs, these often serve to legitimize the prison system rather than confront its racialized violence.

Moreover, the environmental impact of prisons — including emissions, habitat destruction, and waste — adds to the ecological toll of mass incarceration, further entangling social and environmental injustices and making the defunding of the prison-industrial complex together with the restoration of nature in these environments all the more urgent.

Problem #5: Opportunistic greening as global investment strategy

Fifth, a growing trend of opportunistic greening links NBS to real estate development and global green branding [4]. In cities like Amsterdam, San Francisco, or Vancouver, NBS are implemented in elite districts or as aesthetic complements to high-end housing, emphasizing investment value over community need or ecological function.

This approach favors park-like amenities over ecologically restorative spaces and often ignores the socio-ecological degradation in racialized neighborhoods. Green infrastructure becomes a symbol of exclusivity rather than equity, locking benefits into white, wealthy enclaves.

Reckoning with legacies of systemic violence for NBS

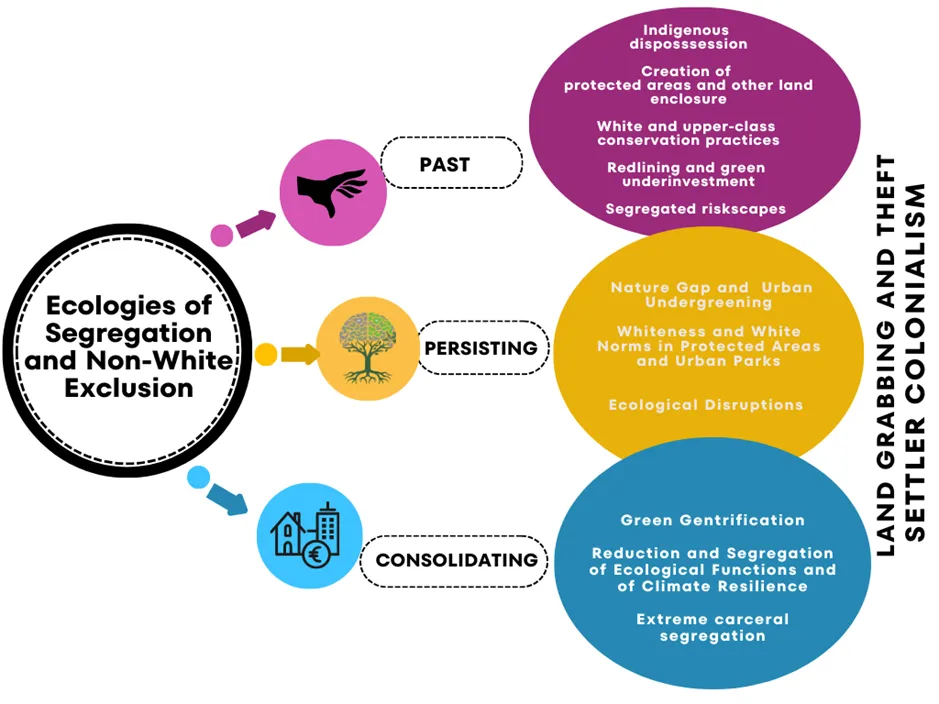

These injustices are not isolated failures but are systemically tied to centuries of racialized land dispossession, settler colonialism, and environmental exclusion, operating through a new phase of what we call green racial capitalism. They form past, emerging, and consolidating ecologies of segregation (Figure 2).

NBS have thus become tools not only for climate action but also for the consolidation of environmental privilege, deepening the divide between those with protected, biodiverse landscapes and those confined to degraded, surveilled, or disappearing spaces.

In contrast, the path forward demands that NBS shift from technocratic solutions to reparative, anti-racist strategies that redistribute land, recognize cultural knowledge, and center the voices of historically marginalized communities.

Figure 2: Framework of past, emerging, and consolidating ecologies of segregation

This blogpost is an adaptation of a forthcoming article in Proceedings of the Natural Academy of Science (PNAS), From past, persisting, and consolidating ecologies of segregation to ecologies of repair, co-authored by Isabelle Anguelovski, James Connolly, Esteve Corbera, David N. Pellow, Fushcia-Ann Hoover, Jacqueline L. Scott, Marccus D. Hendricks, and Chris J. Schell.

Footnotes

[1] Pulido, L. (2017). Geographies of race and ethnicity II: Environmental racism, racial capitalism and state-sanctioned violence. Progress in human geography, 41(4), 524–533.

[2] Anguelovski, I., & Corbera, E. (2023). Integrating justice in nature-based solutions to avoid nature-enabled dispossession. Ambio, 52(1), 45–53.

[3] Anguelovski, I., Connolly, J.J., Cole, H., Garcia-Lamarca, M., Triguero-Mas, M., Baró, F., Martin, N., Conesa, D., Shokry, G., Del Pulgar, C.P. and Ramos, L.A. (2022). Green gentrification in European and North American cities. Nature communications, 13(1), 3816.

[4] A similar case is being studied in the NATURESCAPES project, through the real estate investment proposal in Berlin’s Tempelhofer Feld. Learn more about the conflict here: https://www.thf100.de/

Author: Isabelle Anguelovski

Isabelle is an urban planner and geographer working on environmental justice, green gentrification, and just climate adaptation. She co-leads the Barcelona Lab for Urban Environmental Justice and Sustainability (BCNUEJ) at ICTA-UAB (Institute of Environmental Sciences and Technology, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona).